A fresh lens A fresh lens A fresh lens

A UW librarian creates a canon of meaningful representation of queer and trans people of color in American cinema.

A UW librarian creates a canon of meaningful representation of queer and trans people of color in American cinema.

As a teenager, Michael Mungin, a research and instruction librarian at UW Bothell, would go to Columbia City Library in South Seattle to find books and films about the intersecting complexities of being Black and gay, or what he called as a teenager, “same-gender loving.” Fortunately, some helpful librarians supported his pursuit by setting aside things that they thought he would find interesting. He realized libraries can be a useful safe space and can point people toward resources that might make an impact in their lives. The experience stayed with him and has culminated in the work he is doing now.

According to Mungin, discovering films that center the experiences of queer and trans people of color (QTPOC) may have saved his life. “I think the lack of representation robs you of your imagination for your own future,” he says. But when he was 13, he discovered the 1996 documentary “All God’s Children.” The short film explores the way Black Christian families with gay and lesbian family members are able to reconcile their faith with their family member’s sexuality. The documentary is an example of how people can learn to sit with their discomfort and accept the ones they love as they are. “I remember that really resonating with me because it’s what I had hoped my experience in coming out to my family would be like,” Mungin says. “For me, that film opened a lot of doors in my own mind. ‘Oh, I actually can come out of the closet and people might actually accept me for who I am even if sometimes their faith leads them to say and do bigoted things.’”

In 2018, Mungin was awarded a Carnegie Whitney Grant from the American Library Association in order to create “An Intersectional Lens: Towards a QTPOC Film Canon.” The canon offers a curated list of films that showcase QTPOC in many intersecting and uniquely intimate and eccentric ways of being and loving. At the same time, the films navigate historical oppression and internalized and external racism and homophobia. Mungin organizes the films alphabetically for searchability as well as by race, ethnicity and sexuality in order to further assist those looking for something specific to their personal experience or exploration.

When Mungin began sifting through films, the process required him to review many that represented queer and trans people in exploitative or tokenistic ways. Out of 174 films, just over 60 made the cut for his exploration into authentic QTPOC representation in American cinema. “This is the kind of thing that I wish existed when I was a little younger, when I was a teenager just discovering libraries,” Mungin says. “It was always a struggle for me to find things that spoke to what my future might be.”

“This is the kind of thing that I wish existed when I was a little younger, when I was a teenager just discovering libraries.”

Michael Mungin

Gaps in knowledge, empathy and understanding of lives that are different from the cisgender heterosexual “norm” have been exacerbated by the lack of QTPOC representation in media. Mungin created the resource as a way to remedy this, “and perhaps most importantly for QTPOC to see our own lives reflected in meaningful ways in film,” Mungin explains in the project introduction.

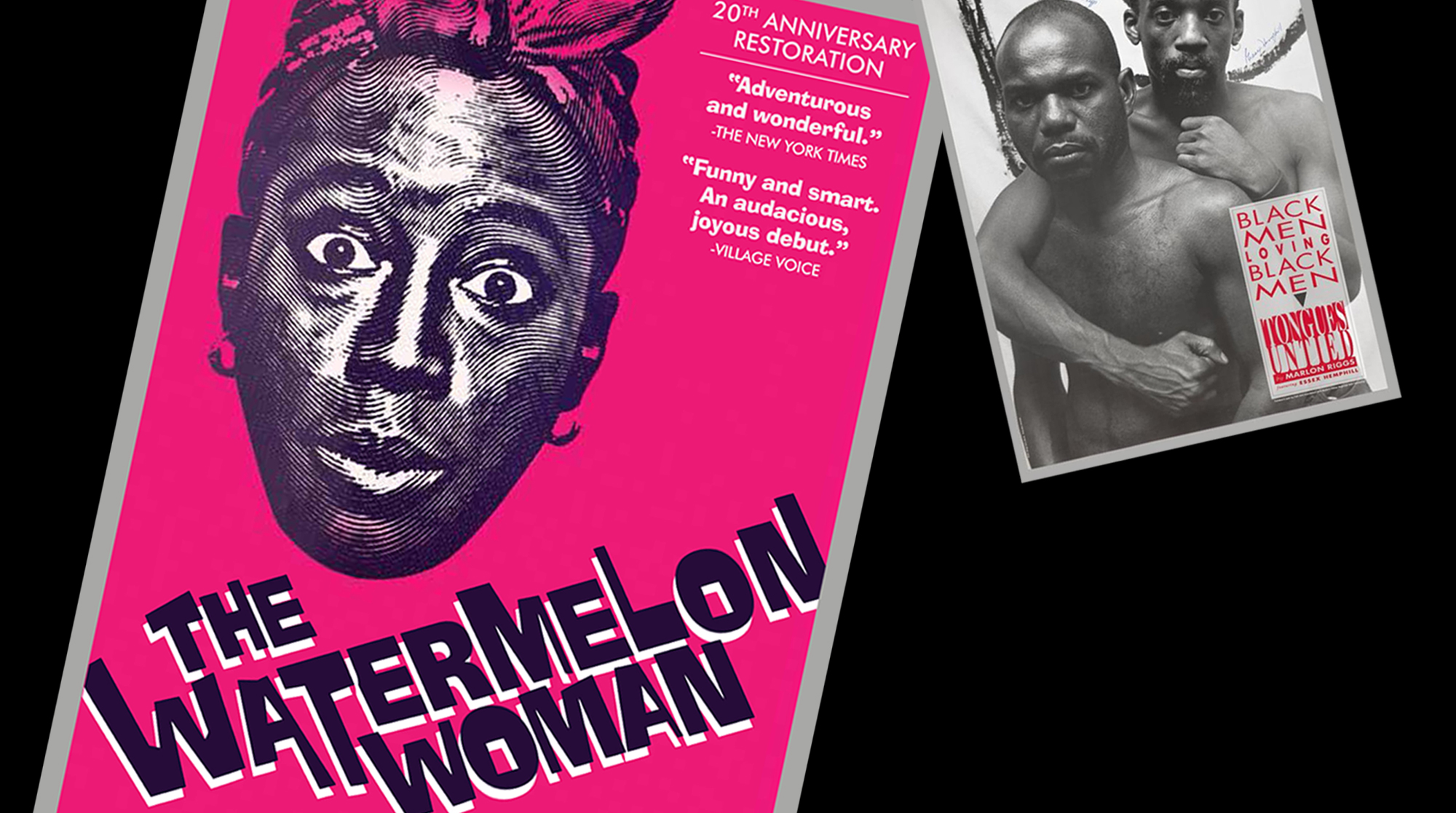

The life-changing impact “All God’s Children” had for Mungin is what he hopes the film canon can have for other QTPOC people who have never seen themselves in film and are looking for real representation. He includes films like “Tongues Untied” by director Marlon Riggs, a documentary about the experiences of Black homosexual men. Conservative U.S. senators and other politicians deemed the movie “pornographic” in an attempt to keep it from airing on PBS in 1991. Riggs responded to efforts to ban the movie from public television in an opinion piece in The New York Times: “Because my film, ‘Tongues Untied,’ affirms the lives and dignity of [Black] gay men, conservatives have found it a convenient target.” He then called the film an expression of “the vitality and significance of a community that traditionally has been silenced and ignored.” The film is in Mungin’s top two. “It is just such an amazing, energetic documentary,” Mungin says. Riggs died from complications of AIDS three years later, but his films have clearly left their mark, and Mungin hopes the online resource he created will contribute to the rediscovery of the work of Riggs and others.

“The Watermelon Woman” by Black lesbian filmmaker Cheryl Dunye is another film Mungin was excited to include. “Cheryl Dunye changed the entire landscape of queer cinema with this monumentally influential and uproarious comedy,” Mungin writes in his description. “The film uses that actress, dubbed “the watermelon woman,” as a jumping-off point to discuss Hollywood’s paradoxical obsessions with both fetishizing Black people and erasing them from view.”

“The Watermelon Woman’s” comedic take on the traumatic experiences of Black lesbians is unique for its time. It is an exception to many of the more emotionally laborious films Mungin discovered. “I had a difficult time about halfway through this project because so many of the films dealt with trauma and with inequity, and sometimes violence,” Mungin says. Since finishing this project, he has struggled to watch any movies in the last year. The sheer volume of films that dealt with various oppressions was overwhelming.

But the emotional labor has not changed Mungin’s view about the project’s importance. Mungin set out to create this resource in part so that the historical marginalization and violence against QTPOC people could be better understood and truly acknowledged. Discourse about race, gender and sexuality can be difficult. What Mungin has created is a virtual space where the films do the talking. QTPOC people can see themselves and their struggles in these films. And white cis-gendered heteronormative people who discover this resource may be able to better understand the depths and many different intersections of discrimination and oppression that QTPOC face.

This representation is especially important right now considering Florida passed an anti-transgender bill called the “Fairness in Women’s Sports Act” on the very first day of Pride Month this year. This is one of more than 250 anti-LGBTQ+ bills, at least 100 of which are specifically anti-trans bills, introduced in state legislatures this year. The legislative discrimination influences—and in many ways emboldens—broader discrimination and violence. By May of this year, at least 28 predominantly Black and Latinx trans and gender-nonconforming people had been murdered, putting 2021 on track to become the deadliest year on record for trans and nonbinary people.

Highlighting films that explore the LGBTQ+ Latin American immigrant experience like “El Canto Del Colibri” and those that examine the biases LGBTQ+ parents experience like “In The Family,” what Mungin accomplished deserves to be celebrated. He acknowledges that his lens is limited to his own life experience, so there may be blind spots to certain communities. He never intended to speak for others but created this canon to “illuminate experiences that have been rendered invisible or marginalized by the centuries-long focus on Caucasian-centered stories, heterosexual-centered stories, and cisgender-centered stories in American mass media.”